Love (and software) conquers all

What is in this post:

- The story behind what motivated me to develop my own app to address a complex travel problem

- How to break down a complex idea to its core and validate the assumptions with minimal effort to help ensure you are on the right path. This thinking can be applied broadly to not only personal but also business problems you are trying to solve.

- Python code examples for the solution to follow along and experiment with the solution yourself (note: does not cover Deepnote and how to set up your Amadeus API account)

They say love makes the world go ’round. In my case, love makes me go around the world. That probably sounds far too philosophical, but this is the story of how my relationship inspired me to create my own travel app.

I did not travel much in my younger years, although I always liked to be on the road. In fact, I spent the first (almost) thirty years of my life living in the same city I grew up in. However, everything changed a couple of years ago when I started travelling a lot for work and was also in a long-distance relationship.

My partner and I spent much of our free time traveling back and forth between our residences in Budapest and Bucharest to see each other and eventually found ourselves falling into a routine — walking the same places in both of our cities, bowling in Bucharest again and again, and eating at the same restaurants.

To shake things up, we decided to visit a different city together to see something new. It was then that we realized how much of a logistical nightmare it was to organize two people traveling to and from the same destination from different starting locations on the same dates — let alone being able to maximize our time spent together in this limited timeframe. And it seemed this was a challenge the travel industry hadn’t tried to address on scale yet, as we could find no existing solutions.

After hours upon hours of research, we were able to make it work, but when it came to finding another destination for our next trip, I thought to myself, “This could be solved in a few lines of code, I’m sure.”

After deciding on Zurich as our next destination, I outlined two key questions to help get the wheels in motion:

- What are the flight schedules from Budapest to Zurich on date X?

- What are the flight schedules from Bucharest to Zurich on the same date?

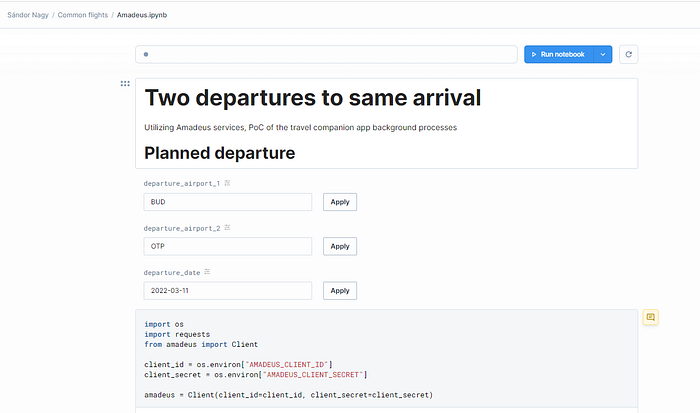

I decided to try something new, so instead of my usual NodeJS/.NET/Java world in which I have more than a decade’s experience, a colleague of mine suggested I try Deepnote. It’s a Python-based online sandbox where the code can be run immediately, and you can write comments and structure it to create a basic user experience. With that in mind, I decided Deepnote would be where I build the first proof of concept:

import o

import requests

from amadeus import Client

client_id = os.environ["AMADEUS_CLIENT_ID"]

client_secret = os.environ["AMADEUS_CLIENT_SECRET"]

amadeus = Client(client_id=client_id, client_secret=client_secret)To have the Amadeus package for the environment, use the terminal for the Deepnote runner to install:

python -m pip install amadeus

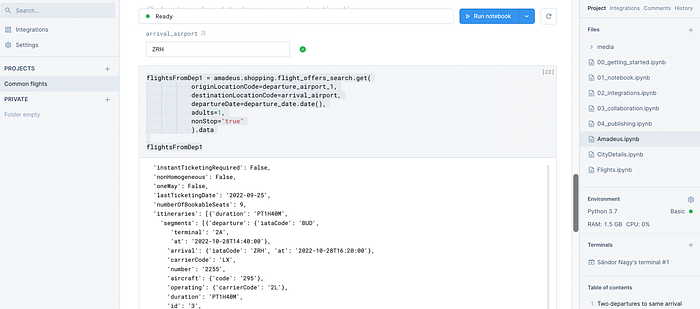

flightsFromDep1 = amadeus.shopping.flight_offers_search.get

originLocationCode=departure_airport_1,

destinationLocationCode=arrival_airport,

departureDate=departure_date.date(),

adults=1,

nonStop="true"

).data

flightsFromDep2 = amadeus.shopping.flight_offers_search.get(

originLocationCode=departure_airport_2,

destinationLocationCode=arrival_airport,

departureDate=departure_date.date(),

adults=1,

nonStop="true"

).dataNow combine the two datasets, using simple Descartes multiplication, pair each flight from Budapest to each flight from Bucharest, calculate the arrival time, and order them:

import numpy as n

import pandas as pd

dflights1 = pd.DataFrame(pd.json_normalize(flightsFromDep1))

dflights2 = pd.DataFrame(pd.json_normalize(flightsFromDep2))

dflights_joined = pd.merge(dflights1, dflights2, how='cross')To look into the structures embedded deep in the itineraries column, I printed the rows in Deepnote:

for index, row in dflights_joined.iterrows():

print(row['itineraries_x'], row['itineraries_y'])

But you can skip the previous two lines and go straight to the time difference between the flights; these were just for myself during the discovery process:

from datetime import datetim

dflights_joined.reset_index()

dict = {

'DiffAtArrival': [],

'From': [],

'FromAt': [],

'FromCarrier': [],

'To': [],

'ToAt': [],

'ToCarrier': []

}

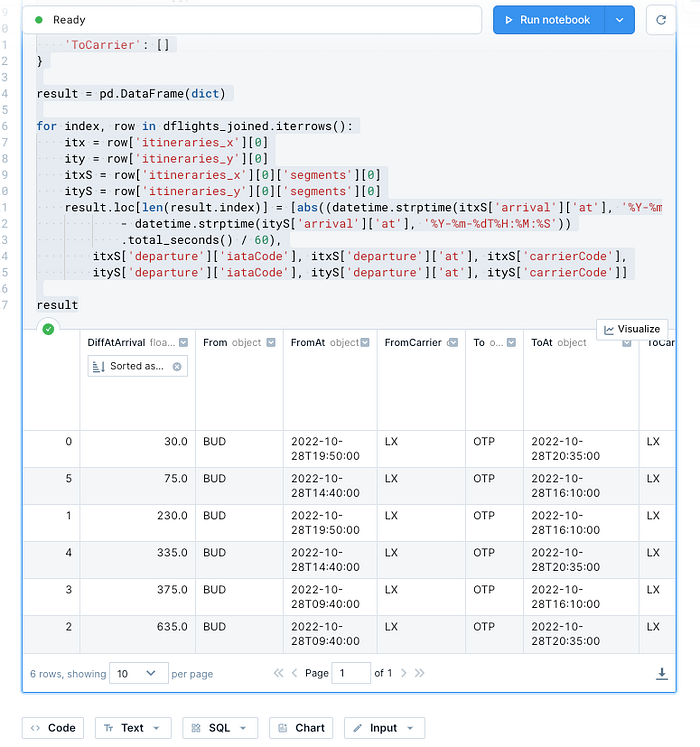

result = pd.DataFrame(dict)

for index, row in dflights_joined.iterrows():

itx = row['itineraries_x'][0]

ity = row['itineraries_y'][0]

itxS = row['itineraries_x'][0]['segments'][0]

ityS = row['itineraries_y'][0]['segments'][0]

result.loc[len(result.index)] = [abs((datetime.strptime(itxS['arrival']['at'], '%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S')

- datetime.strptime(ityS['arrival']['at'], '%Y-%m-%dT%H:%M:%S'))

.total_seconds() / 60),

itxS['departure']['iataCode'], itxS['departure']['at'], itxS['carrierCode'],

ityS['departure']['iataCode'], ityS['departure']['at'], ityS['carrierCode']]

resultI skipped code-level ordering, as Deepnote provided the feature on visualization:

As the results matched the same flight-pairs we bought tickets for, it was clear that the test was a success. We moved onto the fun part — trying unknown values for the variables to see how the solution behaves. I tried entering different dates, and then different cities, then double-checking the solution using live aggregator sites like Skyscanner, which produced similar results.

Going through every European city with an airport would be a huge task for a human, but in Deepnote you can define input fields too and hide the code so anyone can use it, even with a rudimentary UI. In order to test proof of concept, I gave it to my partner who played around with it and found it easy to navigate. If you wanted to, you could even try your solutions on stakeholders, potential customers, friends and family, before even starting to build a complicated application which can give you valuable feedback.

The core of the problem is solved but using the “app” for real still required huge manual effort, which I was trying to avoid in the first place. By trying lots of destination cities and only working with direct flights, it turned out most of the time I didn’t get a response for one of the legs as there were no flights connecting the two cities, which resulted in a new problem statement:

- How can we find the cities that can be reached from two departure airports?

It turned out, one of the APIs I’d tested had an endpoint for the cities that can be served, so I used it once:

servedFromDeparture1 = amadeus.shopping.flight_destinations.get(origin=departure_airport_1

directDestinationsFromDeparture1 = amadeus.get('/v1/airport/direct-destinations',

departureAirportCode=departure_airport_1).dataAnd twice:

servedFromDeparture2 = amadeus.shopping.flight_destinations.get(origin=departure_airport_2

directDestinationsFromDeparture2 = amadeus.get('/v1/airport/direct-destinations',

departureAirportCode=departure_airport_2).data

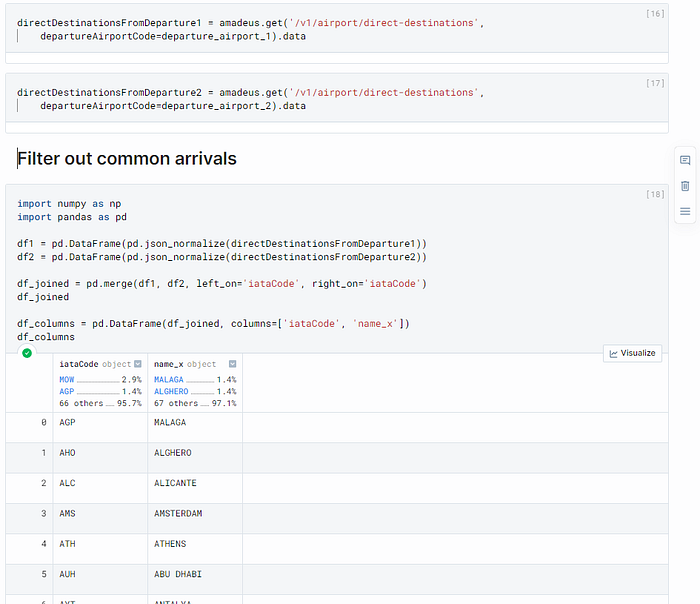

And then combined the results to find a common city that could be found in both lists:

import numpy as n

import pandas as pd

df1 = pd.DataFrame(pd.json_normalize(directDestinationsFromDeparture1))

df2 = pd.DataFrame(pd.json_normalize(directDestinationsFromDeparture2))

df_joined = pd.merge(df1, df2, left_on='iataCode', right_on='iataCode')

df_columns = pd.DataFrame(df_joined, columns=['iataCode', 'name_x'])

df_columns.rename(columns={'name_x': 'name'}).to_json(orient='records')

Even though I managed to narrow it down to far fewer results than previous flight searches, I still found around 50–60 cities, so more than enough to keep my partner and I going for a while. We’ve continued using the app, even for more complex logistical issues — we decided to fly much further afield and needed to find a city where we could meet for a stopover before departing together for our final destination. In the end we managed to find two flights to Madrid, landing just minutes apart and spent the weekend there before travelling on together to the next destination.

Although the app is far from the finished product yet, it’s still proven hugely valuable to us. It’s removed significant time spent on manually locating destinations with mutually convenient flights so the impact has been proven even with such a basic solution. Hours of manual work have been replaced by seconds of waiting, while the output was increased tenfold. It goes to show the power of creative software engineering when standard solutions don’t resolve an issue you’re facing.

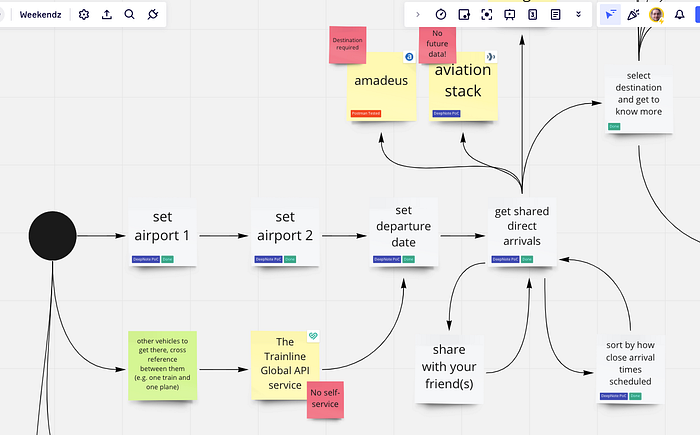

As a sidenote, while working on the code, my mind was continuously racing to new problems around travel. Which city to choose? What to do at the destination when we get there? What if one of us is in a different city? (I travel a lot due to my job and can work on a project in a different part of the world for months.) When this happens, to keep me focused on a single problem, creating a mind map, noting down the ideas helps me to organize them — so I made a Miro board, structured around my problem and the possible decisions.

Insights:

- Focus on small but impactful problems: searching for common cities resulted in a significant time investment using the websites currently available where the same data could be harvested in different ways.

- Prove the idea first, before building a mobile application or adding a feature to an existing one. A proof of concept can help establish what the actual solution is in much less time.

- Clear goals are important when you solve for a complex problem, as I had only one in mind: spare hours of our time finding the common destinations gave measurable key indicators, the tenfold output and the seconds to answer instead of hours.

- Keep the focus by eliminating whatever is unnecessary: put the ideas into a “backlog”, like I did with the Miro board and knowing your customer deeply is paramount in being able to make informed decisions quickly.

Continue with chapter 2 here: